I zipped up my backpack, gave my professor a grateful handshake, and then walked out the door. It was May 20th, 1930 hours—golden hour outside—and I walked down to my card, got in, and started my commute home. Just like that, my Spring semester was over. The day prior, I had driven into SF early and gotten a hotel near campus. My first final of the day was at 0800, and from the hotel I could wake up at 0700 instead of the 0500 wake-up from home needed to ensure my sometimes hours-long morning commute wouldn’t risk missing the exam. One lesson I had learned over the course of the semester was just how important sleep was. So on the afternoon of May 19th, I drove to SF and checked into my hotel. I went for an hour long walk along the water, got a nice dinner from across the street, and came back up to my room with the intention of going to bed early. But things don’t always go according to plan, and so at 0630 the next morning, I found myself lying in bed, having been unable to fall asleep the entire night.

I got up, checked out, and headed to campus. As someone who has struggled with insomnia my whole life, I know more than most people just how important a good night’s sleep is. And yet, I’ve also learned to function extremely well under significant sleep deprivation. Throughout much of late childhood and early adulthood, I was lucky to get 5 hours of sleep in a single night, and I would routinely have freak nights where I simple couldn’t fall asleep at all. I’ve been prescribed every pharmacologic approach from light-therapy to ambien, cognitive behavioral therapy, and I have at times exercised upwards of 5 hours per day to tire myself out enough to get some rest. And yet—what’s helped the most with my sleep? Toughing it out. It used to be that insomnia would scare me, frustrate me, confuse me—when I would realize I wasn’t falling asleep, my mind would start to race as I worried about the short term and long term consequences, paradoxically making my insomnia worse. Then, two things changed: I started working in EMS (where sleep deprivation is something of a badge of honor), and I began listening to Jocko Willink. As a result of those two changes, everything became flipped internally. Then, I was excited to experience sleep deprivation. The challenge in itself was exciting, and the added difficulty of the physical and mental fatigue I would experience would shape me into a stronger, better person. With time, I learned that I could function well enough without sleep: I wasn’t perfect, but I could survive. In EMS, because of mandatory overtime, you often get a mere 3-4 hours of sleep between shifts; sometimes you work night shifts, and your entire circadian rhythm gets flipped on its head. And yet, you don’t get a pass for being tired; you’re still expected to perform your job well. You don’t get a pat on the back. You don’t get special recognition. It’s what’s expected of you. It’s the minimum. I learned that I need a lot less sleep than I thought. And so the morning of May 20th, when I got out of bed at 0630 without having fallen asleep for a single minute of the night, and walked to the bathroom to get a glass of water, I quietly said to myself: I didn’t sleep at all last night. Good.

And I meant it.

My first final went well. I got to campus around 0715, bought a coffee, and then did about 15 minutes of Anki via a filtered deck of forgotten cards from the last 3 days. The exam was on the anatomy of the respiratory, GI, renal, and reproductive systems, plus the physiology of all of the aforementioned systems, plus metabolism, acid/base balance, fluids, and electrolytes. I felt confident on respiratory, reproductive, and metabolism, good on GI and renal, and simply okay on the rest, and my exam reflected that. I scored an 88%, which should put me somewhere near a low A / high A- for the class. And then I had a significant amount of time to kill, because my next final wasn’t until 1800. I studied for a couple hours with a friend, and then we got lunch to-go, and drove a few minutes to a nearby beach that was also a dog park. We sat on a bench, ate our lunch, and enjoyed overflowing affection from several dogs that stopped to say hi. Then, we drove back, and I headed off to my second final. My second final went quick. I scored a 96%, and just like that my semester was done.

This semester wasn’t the heaviest course-load I’ve ever taken. None of the courses this semester were the most challenging I’ve ever taken. But it wasn’t easy either. Anatomy and physiology was challenging, because of the sheer workload, the pace at which we covered material, and the fact that I haven’t taken biology since the 8th grade, nor ever taken a chemistry class, period. The ECG Tech class I was taking wasn’t academically challenging, but it meant an extra hour of commuting to a day that already involved 2-3 hours of commuting ; it meant that on Tuesdays and Thursdays I left the house at 6am, and often wasn’t home until 11pm. This semester was absolutely a challenge, but unlike any other time in my academic career, I met that challenge successfully: I didn’t jump off the deep-end, push myself too hard, perform wow-level feats on the first few assignments, only to crash and burn halfway through the semester. I worked hard. I was consistent. And I was efficient. People say that school is ‘a marathon, not a sprint.’ Indeed, the elite marathoner is not the person who has the hardest workouts, or the person with the perfectly optimized training pace tailored to his specific VO2 max. The elite marathoner is the person who consistently puts in the miles, every single week: The elite marathoner embodies consistency. His VO2 max workouts may not be ‘optimized’ and some days he might not have the energy to complete that extra rep. But he’s consistent. School requires the same.

What follows below are my observations, notes, and lessons learned from this semester.

Early in the Semester: Sleep and schedule.

For the first half of the semester, I woke up between 0430 and 0530 most days, went straight to the gym, and spent around 1-1.5 hours working out before heading to campus. This guaranteed that I got my workout done. However, as the semester went on, I realized that I focus much better in the morning. In the early morning, I can sit through 2 hours of Anki cards without needing to get up or take a break. In the afternoons, I am much more restless, and often struggle to focus for more than 10-25 minutes. Going to the gym in the morning did have some benefits to my focus – I feel good on the days I work out, and that early morning session would often put me in a better mood, which lends itself to studying. But ADHD can be unforgiving, and the morning is the only time when I can consistently focus for extended periods of time; and so in the second half of the semester, I switched to getting all of my focus-intensive studying done early in the morning

I’ve also, in learning how to work around ADHD, become a lot more protective of my attention span. Now, I keep my phone on DND almost the entire day. I don’t check my phone for the first 30 minutes of my morning. I check it once before I start studying, and then put it in a separate room, and don’t look at it again until I’ve finished all of the important focus-intensive studying for the day. I got rid of instagram, and stay off of most social media, including YouTube. Terms like “dopamine addiction” and “dopamine hijacking” get thrown around a lot these days, and while I don’t know if there is a basis of research to support those ideas, I do know that spending ten minutes mindlessly scrolling through instagram reels makes me feel awful in a way few things can, and so I avoid digital distractions like the plague.

Similarly, I noticed pretty quickly that my focus, and mood are much better when I’ve gotten a good night’s sleep, and so much of my schedule and life is heavily centered around getting a good night’s sleep as well. And as I understand the theory of learning, sleep plays a very important role in the function of your memory. As such, I rarely drink alcohol, which significantly effects my sleep. I do drink caffeine, which I limit to a 16 oz of coffee in the morning. I go beyond that only on days when I need it, such as when I have two final exams and got a total of zero sleep the night before.

Studying and workflow

Most of my college career up until this semester has been studying math, and my grades when I went to UC Berkeley were Bs and Cs on a good day, so I knew that this semester I was in for a very difficult learning curve. Thus, I spent a significant amount of time early in the semester researching both how to learn effectively, and how to be successful in the specific setting of a lab-based STEM course like Anatomy or Physiology. What I found is the following: Success in such a course requires three skills: Learning ability, remembering ability, and exam performance.

Exam performance is simple to understand: Exam-taking involves more than just understanding a concept. It involves being able to rule in or out options; being able to read between the lines; and being able to distinguish between what’s ‘textbook’ and what’s ‘real world.’ And to get better at taking exams, you take exams. Lots of them. Learning ability is the ability to, when given all the requisite information, piece together the why behind something. This comes easy to me, because it’s mostly a skill of logical reasoning, and my training as a mathematician makes that feel natural.

What I struggle with is remembering: My memory isn’t great. Maybe it’s a function of my ADHD. Maybe it’s just how I am. Regardless, I might understand something easily, but I forget it so quickly that even an hour later I’m confused and unable to explain even the simplest concept. And so I dived into the science of memory and learning, and ultimately came across two main concepts that I believe are central to remembering what you learn: Spaced repetition and active recall.

Spaced repetition is the concept that, when studying a concept, your brain will remember the information better if you space out your studying. In other words, the person who studies for 1 hour each week for 3 weeks for an exam will remember more than the person who studies in only one 3 hour block the day before the exam. Active recall means studying by actively retrieving information from your memory. For example, explaining to a classmate the relationship between the hypothalamus and pituitary gland without looking at your notes. Answering flashcards is also active recall. On the other hand, highlighting your textbook is a passive process. Highlighting tests—and trains—your ability to recognize that information is important, not your ability to retrieve that information from your memory.

Very early on into the semester, I decided to completely buy in to the ideas of spaced repetition and active recall. I made them my life, structuring my entire study routine around them, and was rewarded for doing so:

My workflow for the semester was as follows:

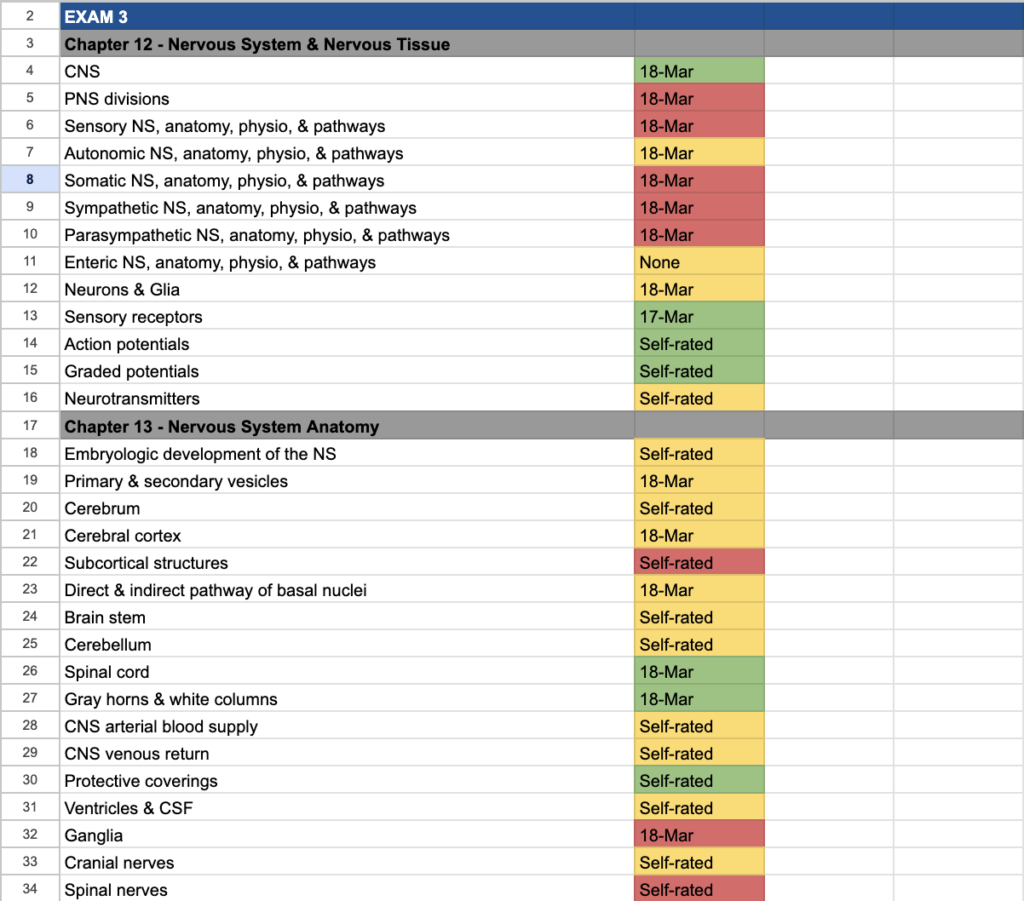

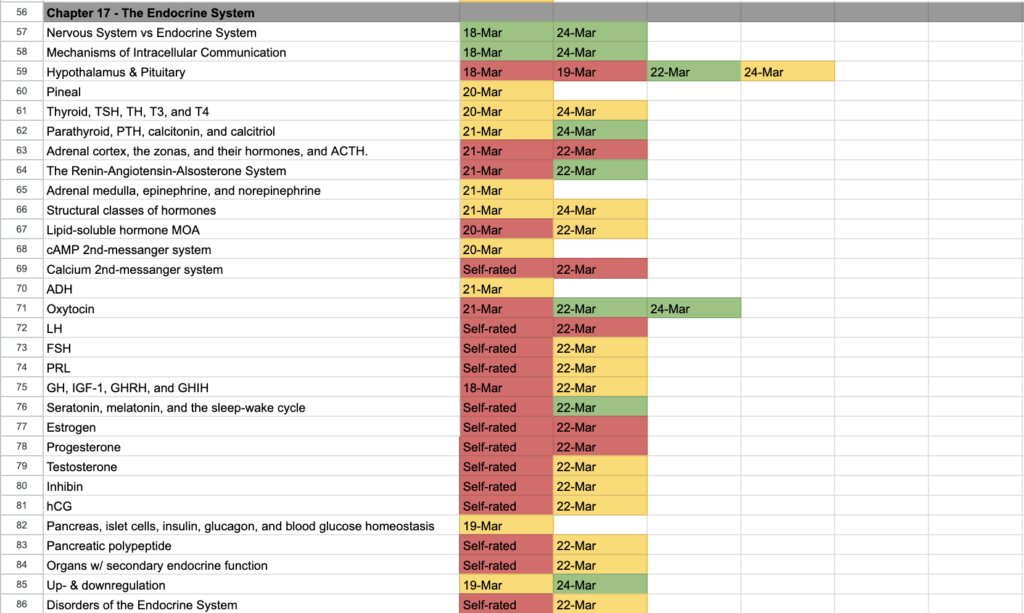

First, I scoped1 each chapter by making a list of all the major topics in that section. These I put into a spreadsheet, and separately, as headings in a google doc.

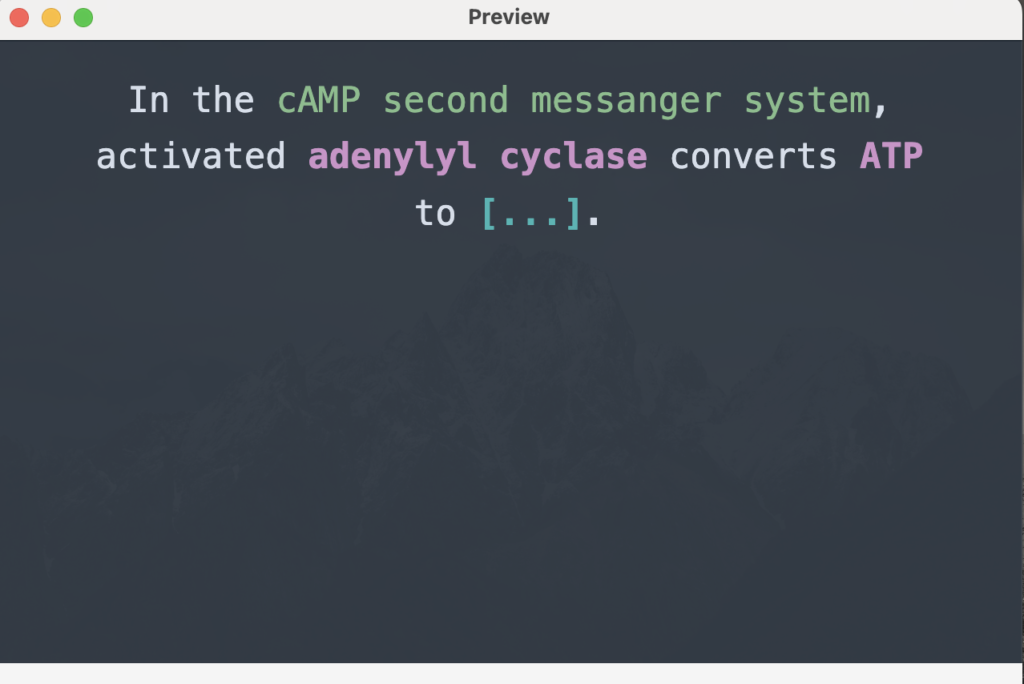

Then, I went through the chapter again. As I did so, I made Anki cards (I made around 7,500 total over the semester) and review questions that I could return to later to study with.

Then, I did the Anki cards, and answered the review questions.

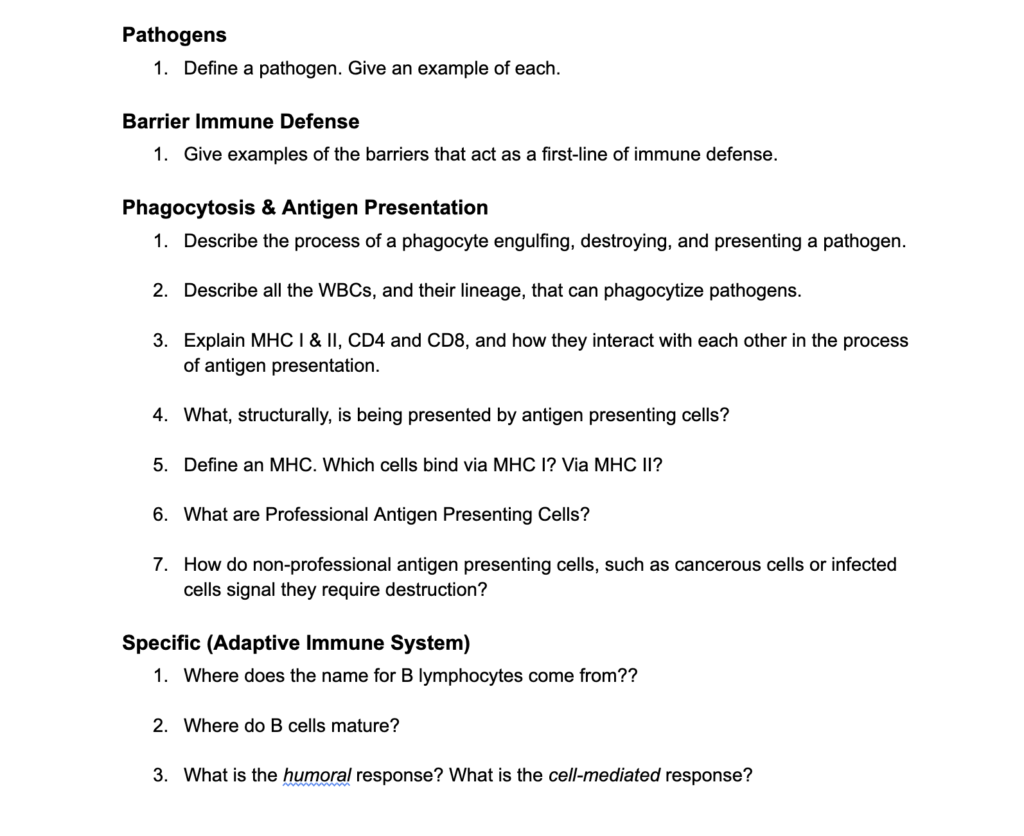

About two weeks out from the exam, I would switch to using the review questions a lot less, and would use practice problems from the textbook, or Guyton & Hall Review 14e, which I bought for around $30, for exam-specific preparation.

Using Ali Abdaal’s Retrospective Revision Timetable, I would review each topic on the scope list, and rate it red/yellow/green according to whether or not I was weak/okay/strong on that topic.

Then, I would study the red topics first, doing so until they became yellows. Then, I would do yellows until they became greens, and so on.

If I had extra time, I would start reading ahead and making cards / review questions for future chapters.

Time Management

Throughout the day, I would always do my Anki reviews, and then new cards first. Then I would spend the remaining time I had reviewing material. I actually endeavored to always stay 1-2 chapters ahead during the semester, and that made all the difference in the world: Simply having an extra week to review because I started a week early made a huge difference. And, because I had gotten so much reviewing done on the back-end, when exams came around, I was able to take the day or two leading up to the exam easy, and only do Anki cards on those days.

Two thirds of the way through the semester, I did deviate from this workflow slightly: I paid for an Ankihub subscription and downloaded the Anking Step Deck, and instead of continuing to make Anki cards from the textbook we used, I almost exclusively used the Costanzo cards in the Step 1 tag. This saved me an extraordinary amount of time, and I actually wish I did so sooner.

For the Anki nitty-gritty

I had two decks throughout the semester. My ‘CURRENT BLOCK’ deck had an FSRS retention of 95%, and contained all the cards relevant to the upcoming exam. My ‘LONG TERM’ deck had a retention of 85% and contained all the cards from past exams. I optimized FSRS about once per month, and initially let it choose my learning steps using the FSRS helper add-on, but later moved to steps of 2m 10m, which ultimately I think improved my shorter-term retention, which helped for content learned in the last few days leading up to an exam.

In total, I did around 70,000 reviews over the semester, with a longest streak of 61 days in a row. I averaged around 450 reviews per day on days studied, though in the latter half of the semester I was averaging between 700 and 1,000 reviews per day. In terms of duration, I spent about 7.5 days (168 hours) total doing Anki, and matured about 5,500 of the cards reviewed. I generally did about 100 new cards per day, but if I was starting to get a backlog of new cards created, I would increase that to around 150. Moreover, my exam performance seemed to match my retention quite nicely. Exams 1-4, where I got through every card, my grades were around 95%, the same as my retention. Exam 5, I had dropped my retention down to 93%, and hadn’t covered every card: I did every Repro card, and half of Resp, but only a third each of the GI and Renal Costanzo tags, and my score on that exam was 88%.

The importance of rest

One thing that I didn’t do very well over the semester was take breaks. Aside from taking the day after each exam off, I don’t think I took a single day off the entire first half of the semester, and I think it contributed to some burnout later on in the semester. If I could go back, I would have liked to take one day every week entirely off (excepting Anki reviews, of course). It’s not that I didn’t have any fun—I still went out throughout the semester, going on dates, hanging out with friends, and doing the hobbies I enjoy. But I rarely took a full day off, and in retrospect, that did wear me down.

I practically lived, breathed, and dreamed anatomy and physiology for most of the Spring 2025 semester, and in doing so I nurtured a profound passion for both subjects: When I got home from a long day of studying, I didn’t want to rest: I would eagerly throw on the podcast The Poison Lab, and learn about membrane physiology, proton pump inhibitors, or the blood-brain barrier. And even though I’m currently on break, I find myself spending a lot of time reading about the physiologic topics that are interesting to me, doing practice problems, and of course, my daily Anki cards. I’ve wanted to go to med school for a long time; the passion has been there from the very first ride-along I did in EMS, before I had even become an EMT. But up until this semester, I never thought I could actually do it. I’m not equating the difficulty of this semester to medical school or the semesters ahead of me by any means. But for the first time in my life, I’ve myself shown that I can be a successful student; that I can get good grades without destroying my mental health in the process. And so because of that, I’m taking the leap to pursue the dream of medical school. I have no idea if I’ll have what it takes to ever get accepted, but I’m going to give it everything I’ve got, and I’m genuinely excited for the work that’s ahead of me.

What’s next for me?

This summer I’ll be taking Chem 1A at UC Berkeley. I’m already spending a pretty significant amount of my time each day studying to build a solid foundation for that class, since I’ve never taken a chemistry class before (even in highschool). I’ll also be tutoring Anatomy and Physiology for a class over the summer, which I’m so excited for! There are few things that sound more fun to me than getting to spend hours discussing membrane potentials, hormones and their feedback cycles, or any of the other fascinating topics I’ve learned.

After this summer, I have no idea what’s next. But in the meantime, between my daily early morning chemistry experiments, and the Sisyphean struggle of an FSRS retention > 90%, I’ll be living and breathing chemistry, and trying to fit the occasional EKG or toxidrome into the spaces in between.